It wasn’t too long ago that a popular game show appeared on television by the name of To Tell the Truth. It featured a person of note and two others masquerading as him. Some readers may remember it, others may not. Regardless, the show’s host (Bud Collyer and later Gary Moore) concluded each round of questioning by the celebrity panel with, “Will the real so-and-so please stand up?”

The question is surprisingly apropos in the wake of new martial arts movies dealing with that latest martial craze, ninjitsu – or ninjutsu, depending upon your preference. It is also apparent that ninjitsu as a trend is here to stay.

The question is surprisingly apropos in the wake of new martial arts movies dealing with that latest martial craze, ninjitsu – or ninjutsu, depending upon your preference. It is also apparent that ninjitsu as a trend is here to stay.

Where does ninjitsu come from? What are its origins? And how did Hollywood latch on to this latest martial phenomenon?

Historically, ninjitsu, as a fighting art, was developed by Japanese mystics in the Iga and Koga regions of ancient Japan. Today, it is still taught by a select group of masters who advocate the total encompassing picture of philosophy and fighting that make up this ancient style (for a more detailed discussion, see Ninja, Spirit of the Shadow Warrior by Stephen Hayes, Ohara Books).

As for Hollywood, it too has found this exotic martial arts form very much to its liking. A number of recent films have employed the “ninja mystique” as the backdrop to action and adventure. Among them: Chuck Norris’ The Octagon; Enter the Ninja; and Revenge of the Ninja. The last two star martial artist/actor Sho Kosugi and appropriately we begin our discussion of the subject with him.

As for Hollywood, it too has found this exotic martial arts form very much to its liking. A number of recent films have employed the “ninja mystique” as the backdrop to action and adventure. Among them: Chuck Norris’ The Octagon; Enter the Ninja; and Revenge of the Ninja. The last two star martial artist/actor Sho Kosugi and appropriately we begin our discussion of the subject with him.

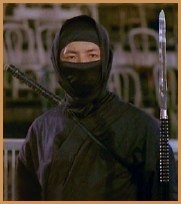

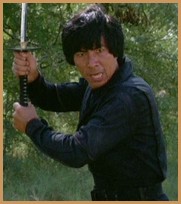

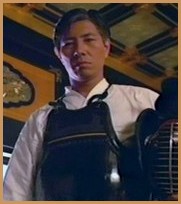

For Kosugi, a transplanted Japanese martial artist currently teaching in San Gabriel, California, the two films offered a chance to show his acting versatility as well as martial arts diversity. As the antagonist in Enter the Ninja, Kosugi demonstrated the fighting art in all its deadly potential. Returning to star in Revenge of the Ninja, Kosugi will be shown as the film’s hero.

How does he feel about portraying a ninja? “Both films are for entertainment,” he replied in answer to the question. “Real-life and entertainment are quite different. Sometimes in dramatics you have to exaggerate, and you can do that in a movie. I’m grateful for the opportunity.” And though what is portrayed is no doubt exaggerated to heighten the films’ entertainment level, the swordplay and fighting stand out dramatically. “But to do so,” added the new star, “you have to have the foundation of the martial arts.”

How does he feel about portraying a ninja? “Both films are for entertainment,” he replied in answer to the question. “Real-life and entertainment are quite different. Sometimes in dramatics you have to exaggerate, and you can do that in a movie. I’m grateful for the opportunity.” And though what is portrayed is no doubt exaggerated to heighten the films’ entertainment level, the swordplay and fighting stand out dramatically. “But to do so,” added the new star, “you have to have the foundation of the martial arts.”

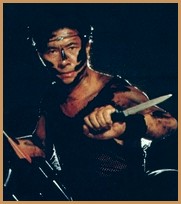

Fortunately, these are two films that attempt to touch those levels. Specifically, the film’s swordplay (choreographed by Mike Stone in Enter the Ninja) demonstrated a realistic adherence to ninja technique. Rather than the elaborate sweeping strokes and movements of a samurai swordsman or karateka, Kosugi and others were well versed in deft ninja technique.

“I worked very hard preparing for this picture and the fighting sequence,” explained Kosugi. “We used a lot of weapons, some which ninja didn’t use and some they did. But they’re all for entertainment. We shot the scenes at regular speed, not at a faster speed. That’s how this film is different from the others. I used a lot of nunchaku, sai, tonfa, and the bo in real-life karate demonstrations and did the same in this film – except the tonfa,” he added. “I know, for example, that ninja didn’t use all those weapons but we wanted to show some exciting techniques. That’s what’s important. In Japan, a lot of films are made about ninjitsu. They show characters disappearing into a cloud of smoke, becoming invisible. That’s ridiculous. But they’re doing it for entertainment. Remember, you’re trying to tell about 500 years of history and legend in about two hours, so much must be exaggerated. If you make your picture fascinating, more people will enjoy it. This is not a documentary; this is entertainment.”

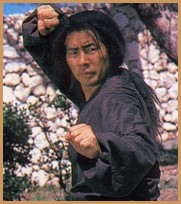

Presenting what was originally conceived as a covert art of killing and espionage is no easy task. Even trying to research the subject can be frustrating. Kosugi, being familiar with ninjitsu somewhat, explained why: “Ninjitsu itself is a very secret process. There are no big fancy movements. They are very small and the art is viewed as espionage; you’ve got to kill your opponent no matter what. Just kill and complete the task, that’s all that’s important. Now ninjitsu is coming out with books, TV coverage, and everything. It used to be, however, that ninjitsu was low class and nobody wanted to know anything about it.”

Presenting what was originally conceived as a covert art of killing and espionage is no easy task. Even trying to research the subject can be frustrating. Kosugi, being familiar with ninjitsu somewhat, explained why: “Ninjitsu itself is a very secret process. There are no big fancy movements. They are very small and the art is viewed as espionage; you’ve got to kill your opponent no matter what. Just kill and complete the task, that’s all that’s important. Now ninjitsu is coming out with books, TV coverage, and everything. It used to be, however, that ninjitsu was low class and nobody wanted to know anything about it.”

Time (and Hollywood, it seems) has a way of putting all things in perspective (and maybe even into a script).

Kosugi’s second film for Cannon, Revenge of the Ninja, will offer more in substance for the burgeoning actor. In it Kosugi will play the hero whose wife, father and child are brutally killed by mobsters staking out a restaurant. They were killed by hired ninja who came to assassinate the restaurant’s owner. Kosugi arrives on the scene only to find his son the sole survivor. What follows is their attempted revenge.

Kosugi’s second film for Cannon, Revenge of the Ninja, will offer more in substance for the burgeoning actor. In it Kosugi will play the hero whose wife, father and child are brutally killed by mobsters staking out a restaurant. They were killed by hired ninja who came to assassinate the restaurant’s owner. Kosugi arrives on the scene only to find his son the sole survivor. What follows is their attempted revenge.

“The main thing is that this is a story of revenge,” Kosugi offered while discussing the upcoming movie. “I don’t think the ninja concept is all that important. The producers just see it as something exciting to explore and use instead of traditional karate. The story is one of revenge. The developments are the same as people may have seen in other movies; the causes and motivations will hopefully be different and intriguing. Instead of using eastern and traditional karate tactics, we’ll use ninja techniques.”

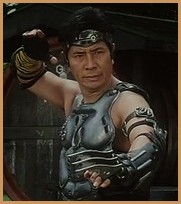

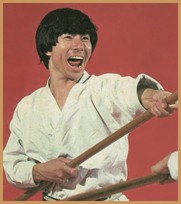

Ironically, it was with traditional training that Kosugi began his career in the martial arts. He, like many Japanese youngsters, started with traditional karate, kendo and judo classes. From there, he continued in other athletic endeavors such as baseball and gymnastics. But always lurking in the back of his mind was the desire to act, even at a tender young age.

Ironically, it was with traditional training that Kosugi began his career in the martial arts. He, like many Japanese youngsters, started with traditional karate, kendo and judo classes. From there, he continued in other athletic endeavors such as baseball and gymnastics. But always lurking in the back of his mind was the desire to act, even at a tender young age.

“I was interested,” he confessed, “but I remember the teacher saying I was no good while I was in grade school. She said I couldn’t act; I was too active she said and to ‘Forget it, you don’t have any talent.’ For six months I went there with no talent.”

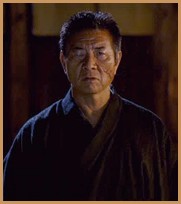

Roughly 25 years later, Kosugi finds himself on the meteoric rise that others have taken. From co-star in Enter the Ninja to star in Revenge of the Ninja he is well aware of the pitfalls and conflics that may soon arise. But he looks at them with a true martial spirit – one of practicality and confidence.

When asked if he feared the response of his students and possibly losing some because of his “celebrity status” he was quick to reply:

“I am concerned about that,” he confessed, “but on the other hand when my students see the movie they’ll say, ‘that’s my teacher’ and that’s exciting for them.”

“I am concerned about that,” he confessed, “but on the other hand when my students see the movie they’ll say, ‘that’s my teacher’ and that’s exciting for them.”

What if a student says he or she wants to learn the things they saw in the movie?

“I’m not going to stop them if they’re at that level. I’m going to train them as a martial arts teacher, not an actor though. I can’t force anyone to do something my way; it’s got to be voluntary. Suppose you like oranges,” Kosugi suggested, “and I like apples. I can’t force you to like apples if you don’t want to and you can’t force me to like oranges. It all depends on the person and how they’re going to take it. In other words, I won’t mind if you start to like oranges. But don’t say that they’re no good and that it has to be done this way. It’s important to face the facts and see these films and their techniques for what they are – acting. You have to have the basics,” the instructor added. “You just can’t jump in there from the first step and expect to reach ten. You have to go to second and then third. Otherwise you’ll get into trouble. You may have the moves and techniques that resemble the martial arts, but they’re really not if you haven’t taken the time to learn the basics and progress though a system. “

And so, while not quite the real ninja – the one who’d proudly rise and claim the truth if he were on our belated game show – Kosugi realizes his responsibilities. And in an age where many a martial artist has been lured by the gold and glitter of Hollywood it is refreshing to see his example. He knows the truth about many of the films that have preceded this particular genre. He also knows that as films they are presented as entertainment with no pretense or false bravado. He is dealing with reality and himself – a man very much in the true martial spirit.

And so, while not quite the real ninja – the one who’d proudly rise and claim the truth if he were on our belated game show – Kosugi realizes his responsibilities. And in an age where many a martial artist has been lured by the gold and glitter of Hollywood it is refreshing to see his example. He knows the truth about many of the films that have preceded this particular genre. He also knows that as films they are presented as entertainment with no pretense or false bravado. He is dealing with reality and himself – a man very much in the true martial spirit.

by Ben Morris

(Published in the October 1981 issue of FIGHTING STARS magazine.)